A Story of Hope

My Recovery Journey after Brain Injury

Introduction by David

The majority of this website tells the story of regaining my life, following a severe brain injury in July 2015 when I was 45 years old.

My injury happened during a leisure bicycle ride from my hometown of Newcastle-under-Lyme in central England, when I was struck at 40mph by a car whose driver didn’t see me.

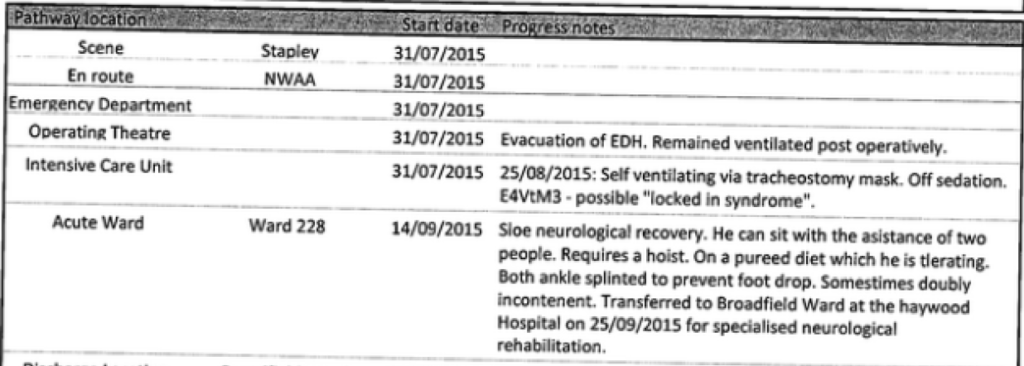

Before browsing further through this website, it may help to view a simplified chronology of events.

Road Traffic Collision

In the following police photo, my head and body made the impression on the car’s windscreen and my bicycle is underneath the front grill. A bystander’s police witness statement describes events at the time of the collision.

I lay comatose in the carriageway, foaming at the mouth and bleeding from my right ear. The incident, which happened near to the town of Nantwich in Cheshire, was reported in the local newspaper.

Air Ambulance Journey

The time critical nature of my head injury led the emergency services to initiate air ambulance transportation from Nantwich to the nearest NHS major trauma centre – the Royal Stoke hospital in Stoke-on-Trent.

I unwittingly tracked my helicopter journey via the GPS tracking app I used on my mobile phone while out cycling. I contributed to an air ambulance charity article; it displays my flight path and duration from data recorded in the app.

I created a selfie video where I expressed my appreciation of the Midlands Air Ambulance charity.

Neurosurgery Operation

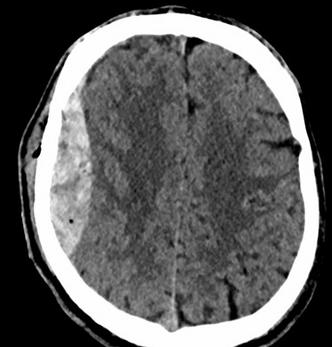

To facilitate the requisite drilling to relieve the pressure from bleeding in my brain (inset photo), my neurosurgeon needed to detach part of my skull, starting at the upper right side of my forehead.

The pressure in my brain was monitored using an Intra-Cranial Pressure (ICP) bolt.

Upon completion of the neurosurgery operation, the removed piece of skull was re-attached and secured with four nylon screws. Three of the screws are under my hair line, while in 2025 one remains partially visible on my forehead.

The records below were made by my neurosurgeon following the operation:

- Right pneumocranium (air inside skull)

- Fracture right parieto-temporal skull

- Large 1.88cm x 8.5cm right temporal extradural haematoma (blood clot)

- 7mm left temporal subdural haematoma

- 1cm contusion (bruise) right midbrain

- Small traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage right precentral sulcus

- Multiple small contusions: Both frontal lobes & left temporal lobe

- Base of skull fracture: right greater wing of sphenoid, extending into left middle cranial fossa & both superior orbital walls

- Scalp laceration

- Facial Injuries: Right zygoma fracture, multiple fractures to lateral and medial wall orbits

- Chest Injuries: Moderate right anterior pneumothorax, extensive right lung contusions upper, mid & lower lobes, fracture right 4th rib, right middle lobe lung lacerations

My passion for the UK National Health Service resulted in my publishing a personal tribute to the NHS.

Black Friday

My life partner kept a diary of my first nine weeks in hospital, which I subsequently transcribed.

Ruth recorded 7th August 2015 as Black Friday – it was 7 days after my brain injury. The expectation was that following rapid health deterioration, I wouldn’t make it through the day. My closest family were brought together at one stage for a consultation and presented with the statement “This is likely to be a life ending event.”

My neurosurgeon’s own assessment of black Friday is evident in my hospital discharge letter. His comment “very nearly died a week into his time in ITU” correlates to Ruth’s observation.

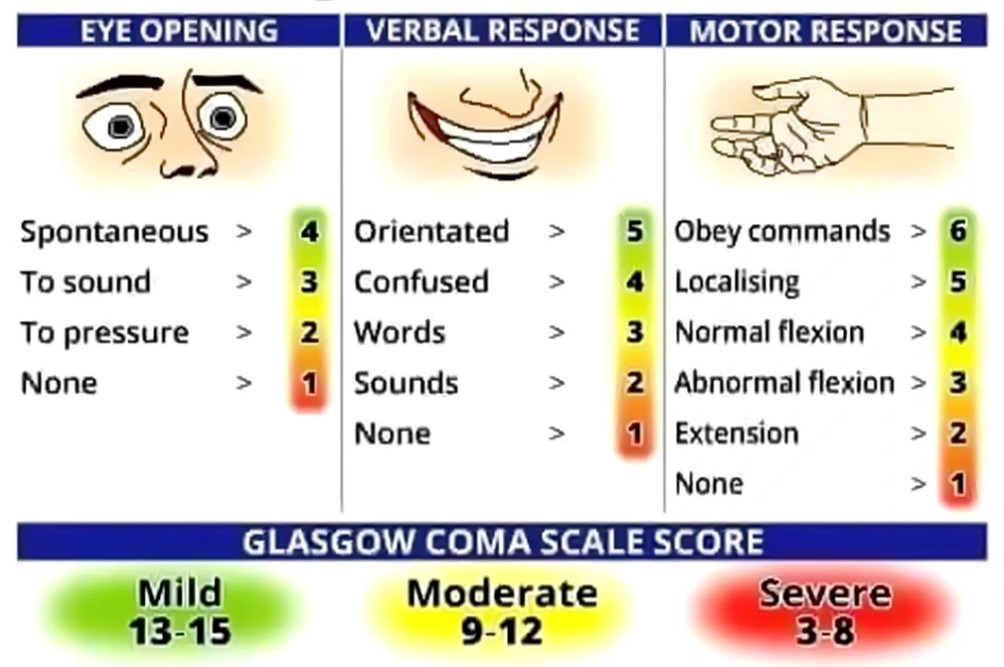

Glasgow Coma Scale

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a method of quantifying the conscious state of someone who’s suffered a brain injury. The following paragraph is taken from a novel by a former NHS doctor – the last statement being dark humour. 😊

“GCS is a measure of conscious level. You get a mark from 1–4 for eye response, 1–5 for verbal response and 1–6 for motor response, giving you a maximum total score of 15 if completely normal and a lowest possible score of 3 if you’re dead.”

I’ve logged my recorded GCS values, as well as a little more explanation about GCS. The highlight being my GCS 3 assessment between 31st July and 15th August 2015.

Locked-In Syndrome

I was comatose for a period of 28 days; the following paragraph is snipped from some email dialogue with Ruth in relation to my emergence from a comatose state.

“People’s general perception is that you just woke up and started asking about simple matters such as sports is very different from mine. I went through a week from hell when you were awake and looking at me, but not talking or responding – and the nurses talking to me about the potential of locked-in syndrome. When they finally had you ‘sitting up’, it was slumped in a special chair, staring at the floor. When finally, you stuttered some words, the first thing I can remember you saying to myself and Chris was… it’s been terrible”

I discovered a rare diseases web site which has clinical information about the condition. Furthermore, there’s a BBC documentary about a man with locked-in syndrome – it has a happy ending. 🙂

Hospital Rehabilitation

I was admitted to the Haywood NHS hospital on 26th September, 2015; it has a special place in my heart – it’s where my life restarted, or indeed I was reborn. I’ve no recollection of my prior 46 days in critical care, or the following 12 days in the neurosurgery ward at the Royal Stoke NHS hospital. Upon discharge for transferral to the Haywood’s complex rehabilitation (Broadfield) ward, my neurosurgeon recorded: “When he left our ward he was babbling, but with no agenda at all – completely disorientated.”

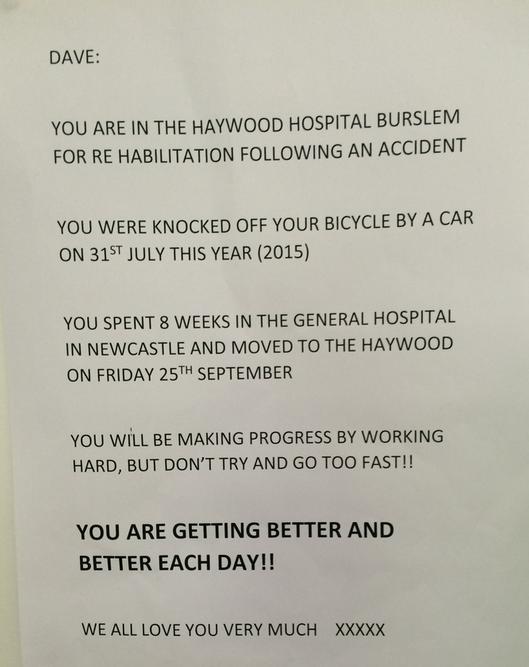

Following my admittance to the Haywood, Ruth printed a note explaining recent matters to me (see image) and pinned it onto a wall adjacent to my bed. I’d read the note 20 or so times each day, it helped enormously to know that people were out there who cared about me. The note is my singular most poignant memory from my time in the Haywood.

I didn’t know why I was in hospital or what year it was, but my cognition was still intact as I was able to use my mobile phone to take the photo.

I’ve probably read the note at least once a week during the 10 years (in 2025) since my injury.

I made the Lego rabbit shown in the photo while at the Haywood; it was intended for 7 year olds, whereas I was 46. It exhausted me, we’ve kept it as a reminder of some of the challenges we faced.

I needed assistance to walk safely – not due to any physical impairment, it was simply because my brain couldn’t send instructions to my limbs to do what I wanted them to. I learned that I’d been doubly incontinent while in critical care; I lost 42lbs (19kg) in weight during the 9 weeks after my injury.

The rehabilitation staff made an enormous contribution to my recovery. I’m extremely grateful to all of them – they are as important as anyone to a successful recovery outcome for a patient. I felt especially close to my rehabilitation folks as they were the first people I engaged with post-injury.

I can summarise my time on the Broadfield ward at the Haywood hospital in one sentence: “I was admitted as a shell of a person, then discharged home just 6 weeks later as David Wozny.”

Clinical Discharge Information

Some of my recorded NHS documentation (which I’ve saved as PDFs) includes the following:

- Royal Stoke hospital (critical care) major trauma summary.

- Broadfield ward (rehabilitation) of the Haywood hospital clinical psychology assessment sent to my GP.

- Haywood rehabilitation consultant’s discharge letter to my GP, containing a clinical summary of my diagnosis and procedures which were carried out on me.

- Post-discharge neuropsychology assessment by a clinical neuropsychologist, following fortnightly two-hour visits.

Neuropsychological Assessment

I was interviewed, tested and assessed by a neuropsychologist 10 months after my Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). A report was produced which incorporated an evaluation of my cognitive function and memory.

The entire exercise was undertaken on a one-to-one basis, taking five hours of effort to complete.

I consider the following observations in the report to be particularly insightful.

- David achieved a mental arithmetic evaluation indicating 99.9th percentile.

- David’s scores for both immediate and delayed recall regarding his day-to-day memory ability were at the 5th percentile.

- The learning disabilities range extends from the 2nd percentile to the 9th percentile.

- A test of effort was administered during the assessment process, Mr Wozny passed all trials on this test. In addition, there were no ‘difficult to explain’ inconsistencies with his responses to the various neuropsychological tests.

The observations were accurate: my short-term memory is dreadful, but I never lost my very good maths skills. I have a PDF of the maths exam paper I took at Staffordshire University in 1993, from where I graduated with a first-class honours degree in engineering.

The tests of effort were based on what appeared to be difficult questions, but were actually simple to answer. Anyone who deliberately tried to fail tests, with the goal of evidencing reduced cognitive capacity for car insurance claim purposes, would be caught out. I like to think of the exercise as truth tests, evidencing that I’m not a liar. 🙂

Personal Views on Brain Injury

I’ve recorded some of my thoughts on being a survivor – the term often used for people who’ve experienced a brain injury.

I personally consider the term survivor relating purely to the short term after the TBI event, rather than the likely ongoing months and years of recovery which many TBI sufferers experience.

I’ve correlated some of my thoughts on how it felt to be brain damaged, as well as what I consider to be pertinent observations.

- You’re unlikely to recover to being exactly the same as you were prior to your injury – accept yourself. In the words of a friend I made during my recovery: “Things are still normal, it’s simply a new normal.”

- Stop apologising repeatedly to people who care about you. The folk around you recognise and accept your limitations, in the simplest of terms they get it!

- You’ll probably experience many worries regarding your future, don’t be afraid to share your anxieties. I prepared a list of some of my anxieties prior to a meeting with my rehabilitation consultant.

- Listen to doctors intently whenever they talk about coping strategies, and be prepared to give them a try.

- Make notes of everything you plan to do, either on paper or a mobile device. Don’t ignore items which seem unimportant, or convince yourself that you won’t forget – you will! I’ve described some of my thoughts regarding short-term memory challenges.

- You don’t need to repeatedly explain that your forgetfulness is the reason you’ve not done something. After the fifth time of retelling your friend or family member about your memory lapse, they don’t need to be told again!

- Sleep is as essential to your well-being as diet or exercise. Ignoring tiredness is counter-productive; having an afternoon nap is good a use of your time.

- Set realistic (low) goals and expectations, baby steps is the sensible approach. It’s understandable that you’d to wish to recover rapidly, that goal is most likely unrealistic.

- Recovery is non-linear, i.e. not a straight line. You can have three good days followed by a rubbish day; it doesn’t mean that you are back at square one.

- You’ll probably be a little different and have some limitations, but you will make it! I’ve described some of my own remaining symptoms / deficiencies.

I Needed to be Needed

The name I’ve used for this web site came unwittingly from my mother, when she was articulating what she saw as the biggest influence on my recovery. My mum had seen me find life purpose through various volunteering roles I became involved in, her exact words were: “You needed to be needed.“

My recovery approach could be expressed in the following phrase: I wanted to feel useful again.

I have a positive life outlook, and consider every lived day beyond my TBI as a bonus. I can summarise my life perspective following my recovery in a single word – contented.